When organizations face pressure to reduce costs, the difference between strategic cuts and damaging ones often comes down to a single factor: the quality of their cost hierarchy design.

Too often, cost hierarchies are either absent or poorly defined. The problem stays hidden until scrutiny intensifies – at which point, the lack of structure blocks informed trade-offs. Without a clear view of discretionary versus non-discretionary spend, organizations find themselves making decisions in the dark.

A well-structured cost hierarchy shouldn’t constrain teams, but provide necessary oversight. It enables control when required. And it can be implemented incrementally. You don’t need to define four layers of granularity from day one. Start with two or three, and extend as maturity improves. Most modern tools support hierarchical cost capture and allow you to add detail over time.

Below are six practical design principles that will help you structure your cost hierarchy for control, visibility, and scalability.

1. Keep structure consistent at every level

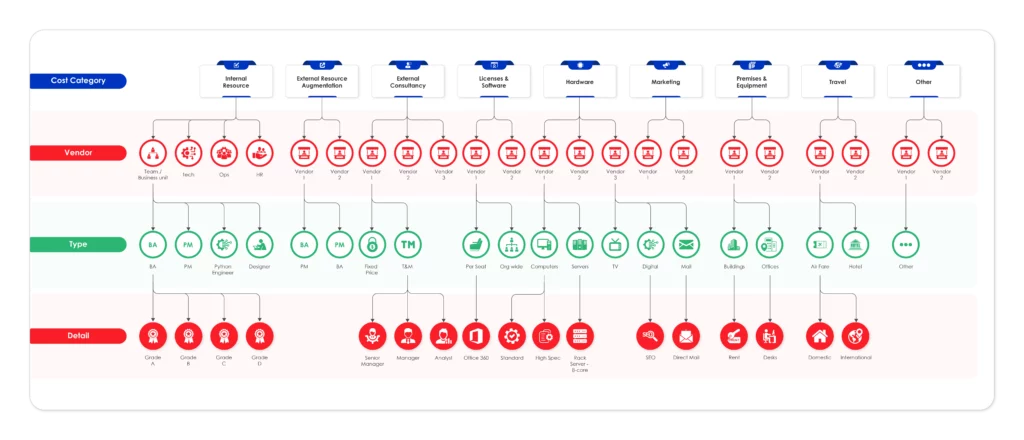

Your hierarchy should have a clear logic from top to bottom. Each level should represent a consistent concept: Category > Vendor > Type > Detail.

When unrelated themes are mixed within a layer – for example, job roles alongside vendor names or pricing models – reporting becomes ambiguous and harder to scale.

This consistency is what allows you to build reporting that makes sense, maintain it as the business grows, and avoid endless workarounds.

2. Push vendor visibility up the hierarchy

In vendor-heavy organizations, vendor relationships must be clearly visible and not buried at the transaction level.

Elevating vendor to a top-level dimension allows you to:

- See fragmentation across your supplier base

- Identify overlapping commercial arrangements

- Consolidate spend for better rates and stronger negotiating positions

This visibility is foundational to any vendor rationalization or commercial optimization initiative.

3. Separate consulting from resource augmentation

There is a material difference between a strategic consulting engagement and a long-running BAU contract for operational delivery.

Lumping both into "Consulting" creates blind spots. One may be discretionary. The other may underpin critical business services.

You need to distinguish between:

- Strategic consulting (high-value, short-term, discretionary)

- Resource augmentation (T&M roles performing day-to-day work)

- Managed services (long-term contracts supporting core operations)

Without this separation, cost-cutting efforts risk hitting the wrong targets – especially as budget ownership decentralizes.

4. Align to your ERP structure

Your cost hierarchy must connect directly with your finance system – whether that’s Oracle, SAP, or another ERP.

Failure to do so results in:

- Forecasting against unapproved suppliers

- Complex reconciliation between delivery and finance

- Limited visibility of actuals

Alignment enables automation. It allows costs to flow cleanly into your portfolio tooling without constant manual intervention. It also ensures project teams are working within approved commercial frameworks.

5. Bias for simplicity. Focus on real cost drivers

Not every cost needs its own category. The goal is aggregation, not precision at the expense of usability.

A good rule of thumb is the 95:5 principle: 95% of spend should be cleanly categorized. The remaining 5% can live in "Other". For example, legal fees likely belong in "Other", not as a standalone category. You’ll always be able to drill into detail if required. But your hierarchy should help you see the wood for the trees, especially when working with billions in spend.

The more categories you add, the harder it becomes to maintain, govern, and report against. Simplicity scales. Over-engineering does not.

6. CapEx, OpEx, and depreciation are attributes – not structure

One of the most common mistakes in cost hierarchy design is trying to bake CapEx and OpEx into the structure itself.

CapEx and OpEx are accounting treatments. Depreciation is a downstream calculation. None of them belong in the hierarchy.

Instead, treat them as attributes assigned to each cost item. This keeps the hierarchy operationally focused, while allowing finance teams to apply the correct accounting standards downstream.

It also reduces the need for delivery teams to interpret capitalization rules – enabling them to focus on execution, not accounting.

Case study: Cost base transformation through structured vendor consolidation

A Tier 1 national bank reduced its IT cost base by 17% in 12 months – not by cutting spend indiscriminately, but by taking control of its vendor landscape.

Previously, the bank was engaging dozens of systems integrators and consulting partners across business units, often with little coordination or consistency. Rates varied wildly, and procurement was reactive.

To address this, the bank issued a strategic RFP to existing partners. The approach was simple:

- Commit to a minimum spend across 5 years

- Remove any cap on upside, allowing vendors to grow their footprint based on performance

- Select five strategic vendors for all core technology work

- Agree standard rate cards and legal terms upfront

- Use a standard mini-RFP process for each new engagement

The result was a cleaner, more manageable vendor ecosystem. Costs came down through competitive pressure, without reducing choice. Vendors deepened their investment in the relationship. Procurement overhead was significantly reduced. And risk of vendor lock-in was mitigated by keeping five active partners in play.

Specialist vendors could still be brought in where needed. But the vast majority of like-for-like technology spend was now flowing through a controlled, structured process – underpinned by a well-designed cost hierarchy.

When cost pressure hits, clarity is currency. A well-built hierarchy gives you both, without slowing your organization down.